Articles

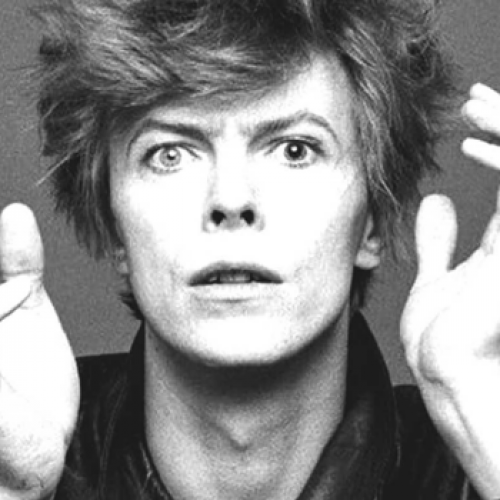

Bowie - and David Jones 1947-2016

Innovation is a concept too narrowly applied in the world of technology and commerce, when it really means a fierce passion for whatever is new or ‘nova.’ Few people have followed the star of curiosity as relentlessly and successfully as David Bowie, who surprised us right up until the end – his last album, Blackstar, was released to an unsuspecting planet two days before he passed away.

Yet when we write about Bowie we are all writing about what he meant to us, selfishly and deeply personally. And he makes that somehow all right.

His inner life was essentially a mystery, which is what he wanted. But his gift was to free our own creativity and sense of boundlessness.

To be so brightly androgynous in the pewter grey light of England’s early 70s invoked and channelled liberation for many thousands – eventually millions - of social and sexual misfits. “You’re not alone.” More amazing is that even if you were in the mainstream you could love him, and many a straight man found him mesmerising and beautiful when he blazed out of our tiny TV screens.

In the past week the good and the great have been asked for their favourite Bowie track. This is normally a lazy page-filling device, though in this case strangely gripping, mainly for what it says about the chooser rather than the chosen. If you are a real music fan, the question will send you into a terrified funk, partly because your response will pigeonhole you, but also because the real genius of Bowie is not so much in bending genders as his artistry as a genre-bender.

So should you bask in the reflected coolness of a number from 1975’s Station to Station, arguably his oddest album? Or show your Krautrock sensibilities by going for something from the Berlin trilogy; or demonstrate your affinity for the common people by nominating ‘Starman’ or a track from the Ziggy era? Then again you could be perverse by choosing a song from the critically reviled Tonight, an album which even Bowie himself described as coming from his ‘Phil Collins years?’ One critic did just this.

You can’t pick one song. It depends what mood, what weather, what time of day, or time of life you’re going through: Bowie has numbers and styles that fit most needs. From vaudeville to space anthems to synthetic art rock, plastic soul, techno, and much more, he’s truly a man for all seasons. He crosses boundaries of art, fashion, mime, theatre, and music and draws on sources as catholic as Nietzsche, Crowley, RD Laing, Stanley Spencer, Tibetan Buddhism, science fiction, Japanese Kabuki theatre, Warhol, and The Beano comics. Who else could compress as much philosophy into a song as he does with ‘Quicksand’, or express the angst of fears of insanity so hauntingly as he does in ‘The Bewlay Brothers’, the last track on Hunky Dory.

We’re left not so much with grief as a feeling of emptiness, one of incalculable loss. You grieve for someone you know, but ache with a sense of personal loss for something that has been taken away, an inner part of you. For me Bowie doesn’t feel as if he blazed into my life like the alien fallen to earth he’s so often hailed as. No, for me, and perhaps for you too, it’s much more intimate than that - he’s simply always been there, close to heart, on the tip of my mind.

Camelian (sic), Comedian, Corinthian, Caricature are words he used (probably) to describe the mentally ill half-brother he looked up to, and they’ve been wheeled out by writers this week to also label him. The Thesaurus-well of adjectives used to encapsulate Bowie has almost dried up - polymath, iconoclast, changeling, outsider, and all the rest.

My favourite descriptors – he created a big enough canvas for us all to paint ourselves onto - are that he was courteous, English and shamanic.

Back in the 1970’s I saw him interviewed several times by crusty old-style media types. The kind of men who were old before their time, and women who you know would rustle their newspapers noisily if anything strange or sensual appeared on their TV screens. Now if you dredge YouTube enough you’ll find cases of him showing his displeasure – justifiably - at the inane and repetitive nature of the questions he was subjected too.

But in most cases he was kind, courteous and respectful, even when he was so obviously the butt of sneering middle class contempt. Who are you, an uneducated Peter Pan with one ‘O’ level, to fly through nursery windows and tell our children to boogie? Or, worse, to encourage them to make themselves up – who knows where that could lead?

Oddly enough, I found his modest charm more powerfully revolutionary than any amount of shouting or violence. He wasn’t trying to ch-ch-change anything: simply by being who he wanted to be, he was lobbing a Molotov Cocktail at the cultural rigidities of the 1970s that even the permissive mores of the 60s had failed to dislodge.

Then there’s his Englishness.

I’m not jingoistic, but I find myself very moved by the impact that this skinny, snaggle-toothed boy from a simple background in south London’s Brixton has had on the world, from Berlin to the Bronx (and of course from Ibiza to the Norfolk Broads).

In a 2002 interview he remarked that his subject matter had always been the same:

‘The trousers may change, but the actual words and subjects (are always) to do with isolation, abandonment, fear, and anxiety – all the high points of one’s life.’

Here I and my fellow Brits can claim some unique understanding – which is that we use irony and humour, while really intensely meaning what we say at the same time.

Bowie’s lyrics, word plays and musical styles are not weakly mid-atlantic. Although he adored The Velvet Underground and American soul, and drew on so many influences, including those from the Far East and European industrial noise textures, he melded it all into a peculiar, distinctly English sound palette. Closer to Vaughan Williams than Elvis, more John Betjeman than Chuck Berry. But often with thunderous guitars…

So when I see flower tributes on the streets of Berlin, and hear the bizarre but rather wonderful claim that he helped bring down the Berlin wall by singing ‘Heroes’ so the East Germans could catch it over the wall in ’86, there’s a catch in my throat. Perhaps at last the world is waking up to the idea that artists like him are far more important agents for change than dull politicians who claim, unconvincingly, to have been ‘rockers’ in their earlier life.

Which brings me to the shaman claim – something I could never defend in intellectual debate, and yet resonates with all that’s intuitive in me. When I said earlier that Bowie’s always been there, it’s remarkable that his presence persists inside me even when I’ve taken a few years off listening, half-forgotten lyrics surfacing in my mind at just the right moment. The last time was three years ago in Berlin, where I’ve worked a number of times recently. Sitting in the back of a taxi and listening to music on shuffle, up popped randomly his only nostalgic song, ‘Where Are We Now?’,r eflecting on his early days in cold war West Berlin.

“I took a train/From Potsdammer Platz .”

I looked out of the car window, and there was …Potsdammer Platz.

The personal memories and ideas this triggered won’t be interesting to you – a God-awful small affair – but it’s enough to say that it made me cry, think and wonder. I always knew that he could do that.

I don’t know Bowie. Surprisingly, for a music nerd, I never saw him live.

But he helped me, and so many of us, to trust our creative selves a little more, above all to understand that if you want to create, then weird is good.

Can you cry for someone you don’t know, as surely his close family, for whom he was plain David Jones, have done? I don’t know; but we can cry for that part of ourselves, lost forever with his passing, while at the same time feeling blessed that he fell to earth.

Nigel Barlow,

Oxford, January 16th 2016